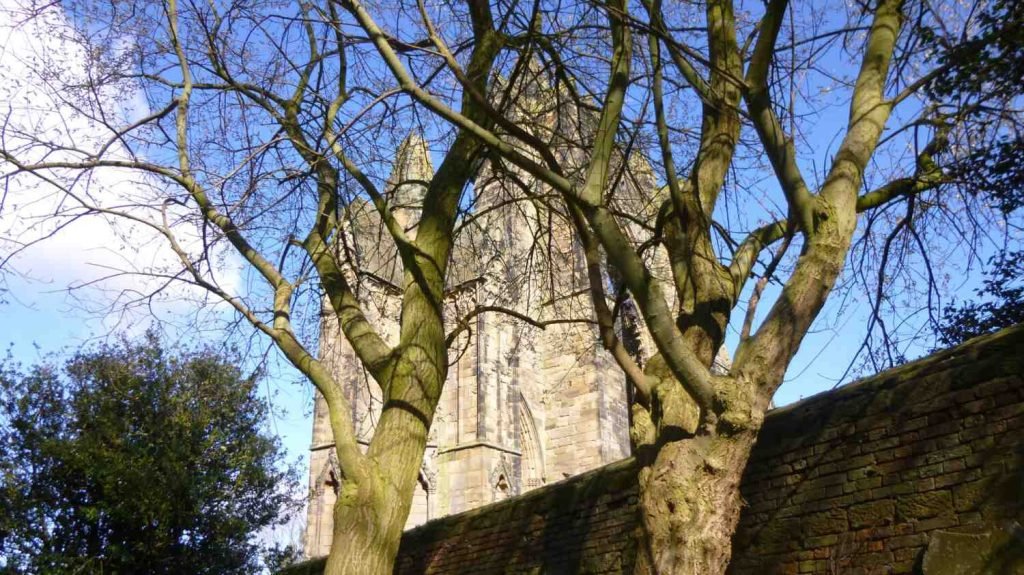

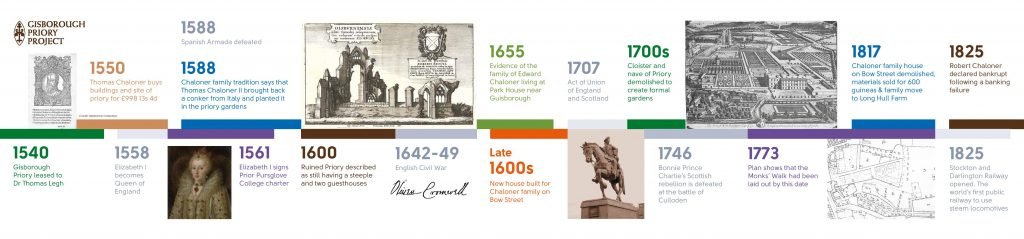

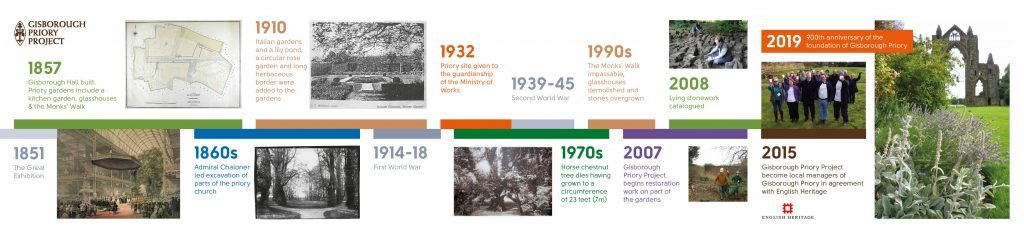

The history of Gisborough Priory covers more than 900 years from its foundation in 1119. After the dissolution in 1540, formal gardens covered much of the site. The gardens became increasingly elaborate but eventually became abandoned. In the late 1990s a local group, which later became Gisborough Priory Project, decided to try to restore at least some of the lost gardens. This article, which is a revised version of an earlier post celebrating the 900th anniversary of the Priory, gives an overview of the rich and fascinating history of the site.

1 – The Medieval Priory (1119 – 1540)

After the arrival of William the Conqueror in 1066, the Normans built many cathedrals and monasteries. Despite this, by the early 1100s there were only four monasteries in the whole of Yorkshire. Two were in York, one in Selby and one in Whitby. Yorkshire was, therefore, ready for a religious revival.

The Augustinian Canons were the first to respond, arriving in England sometime after 1100. Guisborough Priory, which dates from about 1119, was one of their first houses in Yorkshire.

The Foundation

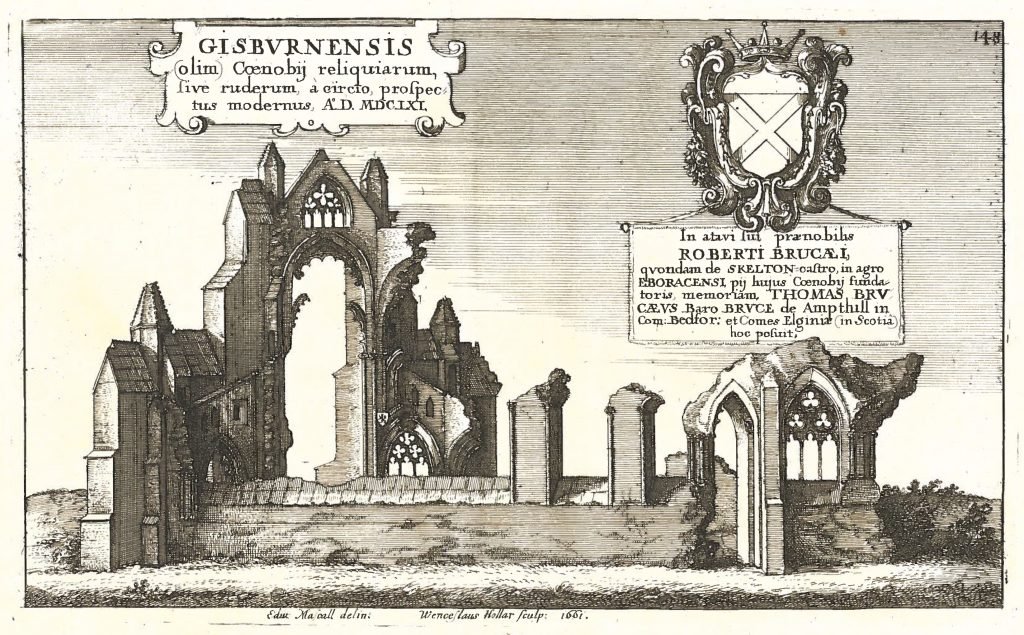

Robert de Brus, who was the most powerful and influential Norman baron in the area, founded the Priory in 1119. He took advice from both the Archbishop of York, Thurstan, and the Pope, Calixtus II, and choose the Augustinian Order. Robert, who was very wealthy, and had large estates in the North East and in Scotland, could afford to give the Priory a lot of land and money. He gave the Canons the whole of Guisborough, about 10,000 acres (4,000 ha) which included almost 2,000 acres (800 ha) of farmland. He also gave them nearby Kirkleatham, (roughly 1,400 acres (600 ha)), part of Coatham and the income from ten churches. With such a good start the Priory could afford the very best, which shows in the quality of the building work. The Canons were also quick to make their mark in the development of the town centre.

The De Brus Family

Robert de Brus expected the Canons to pray for his immortal soul and the souls of all his family. He also intended the Priory to be the family burial place. He died in 1141, and in the third church his tomb was in the Canon’s Quire, in the place of honour. Robert’s sons, Adam and Robert, shared their father’s inheritance, Adam keeping the family home at Skelton Castle and Robert the Scottish lands. Robert II also became the second Lord of Annandale and founded the Scottish branch of the family and was a direct ancestor of King Robert the Bruce. Despite this Gisborough did become the burial place of both sides of the family. The last of the English line was Peter de Brus, who died without children in 1267.

The last of the Scottish branch buried in Gisborough Priory was Robert de Brus, fifth Lord of Annandale, who died in 1295. He was Robert the Bruce’s grandfather and a major figure in Scottish history. He was also known as “the Competitor”, because, as a consequence of the complicated Anglo-Scottish relationships at the time, Edward I, king of England, took it on himself to choose the King of Scotland.

After the death of the first Robert de Brus, the family continued to generously support the Priory. The Canons built up major estates in north Yorkshire, County Durham and Annandale in Scotland as well as Lincolnshire. Their support and encouragement meant that other local families, such as the Percys and the Latimers, also gave generously.

The First Church

The generosity of the de Brus family allowed the Priory to employ the best craftsmen. Work began on the first stone church around 1140 and probably finished around 1180. The first church lies hidden under the present church, but a bit to the south. It had a central tower at the west end, a nave with narrow aisles and a north door with a porch. The plan is similar to the Augustinian Priory church at Christchurch in Dorset.

The Second Church

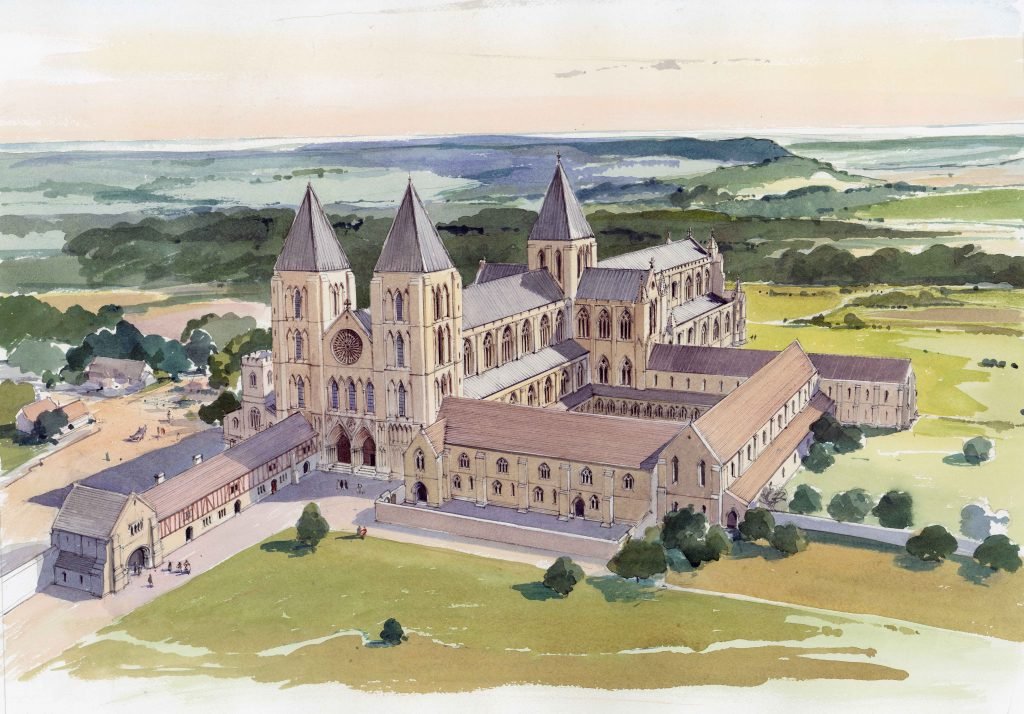

Work on the second church began around 1180, not long after work on the first church finished. The new church replaced the old church which the Canons removed completely before work began. Like most churches, building started at the East End and worked westwards, finishing at the West End in the mid-1200s. This new front had a huge rose window 24 feet (8m) in diameter. A window this big would make it one of the largest “lost” rose windows in the country. The Canons created one of the most richly decorated West Fronts in Yorkshire, if not the whole country.

Inside, the north aisle had chantry, or family, chapels divided by wooden screens and there were many burials. Medieval tiles covered the floor, some are on display in the Custodian’s Hut and others in St Nicholas Church.

The Great Fire, 1289

Work on the second church finished around 1240 but on the 16th May 1289, just before noon, a disastrous fire broke out in the roof. A plumber (described as a “vile plumber…of wicked disposition” by the medieval chronicler Walter of Hemingborough) had been repairing holes in the lead on the roof. When he returned to the church he left his workmen to put out the brazier they had been using. Unfortunately, they did not do this properly, the roof caught light and molten lead and masonry fell into the church. The fire spread and seriously damaged the church; books chalices, vestments and statues were all destroyed. The rebuilding took almost one hundred years and resulted in the third church, which is the one we see today.

Read a detailed account of the fire and its aftermath here.

The Third Church

Rebuilding

Gisborough had always been a wealthy Priory but the 1300s was a very difficult period. Edward II’s defeat at Bannockburn in 1314 meant that the Canon’s lost the income from their many Scottish lands. The Priory also had to accommodate canons from more northerly Priories such as Brinkburn, Hexham and Jedburgh. The Black Death, which arrived in 1348, and an agricultural depression lasting most of the century, made things even worse.

The fire had destroyed most of the inside of the church but many of the walls survived. The roof appeared to suffer a lot of damage but the West Front also survived, although the heat melted the bells in the North-West tower.

At this time the Canons also rebuilt the East End of the Church, making it much longer. The superb East End dates from almost exactly 1300, as does the West Cloister range.

The Final Church

English Heritage’s reconstruction gives a good impression of how the final church must have appeared from the outside. Inside, the rebuilt nave was now relatively clear, there were fewer burials and no chantry chapels. The internal walls were white, possibly painted with red lines to look like masonry, wall paintings told bible stories. The crossing and choir survived from the second church. Robert de Brus and his wife Agnes lay in the place of honour between the Canon’s stalls in the Quire. Further east the new presbytery finished at the new east end. This is an outstanding example of early Northern Gothic architecture and of exceptional quality. There were several chapels at the new East End and a processional walkway passed between them and the high altar.

The De Brus Cenotaph

Although externally the Church remained unaltered until the dissolution, bosses and stonework from the 15th Century show that inside the church continued to develop according to the needs of the Canons. The last but one Prior, James Cockerell (1519-1534), installed the Brus Cenotaph. The Priory closed soon afterwards, in 1540, and the Cenotaph removed. Afterwards it led a tumultuous life, with, at one time, the various parts dispersed widely. Admiral Chaloner recovered the missing pieces and reassembled the Cenotaph in 1907 in the Parish Church, where it still stands.

The Dissolution

By 1535 Gisborough Priory had an annual income of £628 6s and 4d. This made it the fourth richest house in Yorkshire, after York, Fountains and Selby.

The dissolution process began in 1536, when the King’s Commissioners, Thomas Leigh and Richard Leyton arrived at Gisborough. They forced the Prior, James Cockerill, to resign and installed Robert Pursglove in his place. This was unpopular as Cockerill had strong local support and by 1536 some 500 households in the town depended on the Priory for their income. Disliked by both Canons and townsfolk, Pursglove nevertheless remained Prior; he signed the Deed of Surrender, on the 23rd of December 1539, in the Chapter House. Although the Priory was given up at this time the buildings were mothballed for a few months. A proposal to turn the Priory into a collegiate church had been made, which was ultimately unsuccessful, and the Priory was final given to the Kingon the 8th April 1540. 1540 marked the final year of the Dissolution of the Monasteries, Gisborough was theref ore one of the last.

2 – After the Dissolution (1540 – 1825)

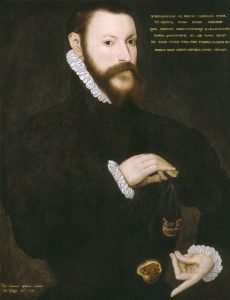

The Priory was first leased to Thomas Leigh later in 1540. Leigh had been one of Henry VIII’s commissioners and oversaw the dissolution of the Priory. He died four years later. Sir Thomas Chaloner obtained the lease when he married Leigh’s widow in 1547. He extended it shortly afterwards before buying the estate outright in 1550.

Sir Thomas Chaloner

by Unknown Flemish artist

oil on panel, 1559

NPG 2445

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Chiswick Church. Monument (3) to the second Sir Thomas Chaloner, 1615.

“Plate 50: Chiswick Church. Finchley Church,” in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Middlesex, (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1937), 50. British History Online, accessed March 27, 2019, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/middx/plate-50.

The Chaloner’s lived mainly in London and Steeple Claydon, Buckinghamshire and did not visit Guisbrough very often. However, the second Thomas Chaloner certainly knew the town as he started the alum industry there. Nevertheless, it was his cousin, also Thomas Chaloner, who actually ran the business. This Thomas, who was from Ireland, lived in Guisborough, possibly after adapting the Priory ruins.

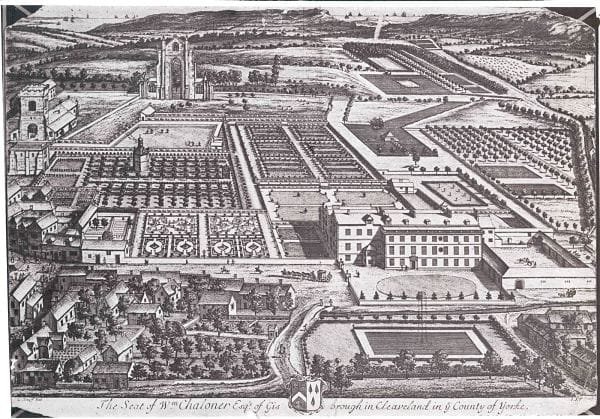

The First Guisborough Hall

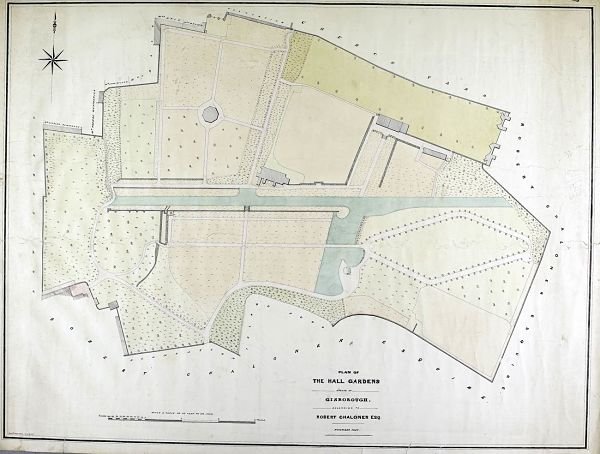

The first of the Chaloners to live in Guisborough was Edward, was there by 1655. At first the family lived outside Guisborough, at Park House, to the north-west. By 1709, however, they lived in a new Hall in the town centre, with gardens incorporating the Priory ruins. The family continued to develop the gardens (the Monks’ Walk dates from the mid-1700s) according to fashion. Unfortunately, the first Hall suffered from damp and became uninhabitable; a London gentleman bought it for the material. He paid 600 guineas (£630) but sold the lead alone for 280 guineas (£294).

3 – 1825 – 2000

After leaving the Hall on Bow Street, the family moved to Long Hull, another house on the estate. Sadly, in 1825, Robert Chaloner became bankrupt when the York bank in which he had a partnership collapsed. The family left Guisborough for a while, and lived in Ireland with Robert’s cousin, Earl Fitzwilliam. Robert paid off his debts before he died in 1842 but he did not return to Guisbrough.

His son, also Robert, did return to Guisborough. He restored the family finances, helped by the arrival of the railway and the discovery of iron on the estate. He died childless in 1855 and the estate passed to his brother Thomas.

Admiral Chaloner

It was Thomas, better known as Captain or Admiral Chaloner, who helped develop Guisborough as a community. He sponsored schools, hospitals and churches and gave Long Hull its well known ship-shaped appearance. He had an interest in history and archaeology and carried out the first recorded excavations on the Priory. Unusually for the time Thomas published his work. The collection of stones near the Monk’s Walk shows his interest in the history of the Priory.

He too died childless in 1884 and the estate passed to his sister’s grandson, Richard Godolphin Walmesley Long, provided that he changed his name to Chaloner. Richard, a well-respected Conservative MP, became a peer in 1917. He took the title Lord Gisborough, a deliberately old fashioned spelling reflecting the history of the town.

Richard Godolphin Walmesley Chaloner, 1st Baron Gisborough

by Bassano Ltd

whole plate glass negative, 29 September 1922

NPG x121919

© National Portrait Gallery, London

The Second Gisborough Hall

Lord Gisborough changed the name of Long Hull to Gisborough Hall. At the same time the family developed the gardens both there and around the Priory. About this time, the formal gardens around the Priory started to become kitchen gardens. However, the Gisboroughs introduced features elsewhere such as the Italian Garden at the west end of the site. The gardens were also home to a horse chestnut tree, said to be the biggest in the country. It was about 8 metres round. Thomas Chaloner II may have planted the tree in the early 1600s from a horse chestnut he brought to England. Sadly the tree blew down in a gale in the 1970s.

With time, the gardens became increasingly difficult to keep up. Lord Gisborough gave the Priory ruins to Care of the Nation in 1932. The Ministry of Works cleared away the gardens in that area and replaced them with grass. There is a story that the workmen used a narrow-gauge railway to the Priory Gatehouse to help with the clearance.

A market garden replaced both the former garden around the dovecote and the area around the Italian Garden. These areas are not open to visitors.

4 – Gisborough Priory Project – the latest history

The rest of the gardens, including the Monks’ Walk, became badly overgrown. Eventually, in July 2007, Gisborough Priory Project (GPP) leased part of the gardens south of the ruins. The group arranged for archaeological investigations to identify the location and extent of any medieval remains. In 2008 GPP began to clear away the dense undergrowth, almost entirely by hand. Visitors can now fully appreciate the Monk’s Walk.

In 2015 English Heritage invited GPP to take over the daily running of the Priory site. This was the first time that English Heritage had worked with a voluntary organisation in this way and GPP continue work in partnership with them. GPP recruits volunteer custodians and gardeners (click here for more information) to open the site to the public, recruiting both volunteer custodians and gardeners in the Woodland Gardens and actively researching the history of the site.

Further reading

- B J D Harrison G and Dixon (editors), Guisborough before 1900, Guisborough 1981

- G Coppack, Guisborough Priory, English Heritage 1993

- Gisborough Priory Project, The Lost Gardens of Gisborough Priory, Guisborough 2008

- D H Heslop, Excavation with the Church at the Augustinian Priory of Gisborough, Cleveland 1985-6 Yorkshire Archaeological Journal vol 67 p 51

- S A Harrison and D H Heslop, Archaeological Survey at the Augustinian Priory of Gisborough, Cleveland, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, Vol 71, 1999, p 89