On the 16th of May 1289 at a little before noon, and just as the Convent was gathering for a procession and mass, a fire broke out on the Priory Church roof. A “vile plumber”, engaged to repair holes in the lead roof, and who had already caused alarm due to his “wicked disposition” and dangerous working practices, left his workmen to put out the charcoal that had been used to heat the iron pans. They, however, quickly followed him; failing to properly extinguish the charcoal which remained aglow and consequently reignited. This set light to other combustible materials they had left on the roof and the fire quickly spread to the joists, causing the lead to melt and the flames to increase so rapidly that the Canons were unable to rescue anything. Walter of Hemingburgh, a medieval chronicler, and one of the Canons at Gisborough, recorded that many theological books and nine expensive chalices as well as vestments and richly decorated images were all lost in the fire which destroyed everything. The Gyseburn bible, held in St John’s College, Cambridge, has an inscription stating that it was given to the Priory in 1332 because the Priory’s own books had been destroyed in the fire.

Plan © English Heritiage

Archaeological excavations at the west end of the church found evidence of the fire on the paving in the north aisle and a large amount of burnt material buried under a later floor in the north west tower, including fragments of a shattered bell, a piece of stone with a burnt floor tile attached and other pieces of stone showing evidence of fire scorching.

There was slight fire reddening on some of the floor slabs in the south aisle and several graves were damaged, apparently by falling masonry, although there was no evidence of burning within them.

The north wall was rebuilt after the fire and all but two of the pillars in the nave date from after the fire.

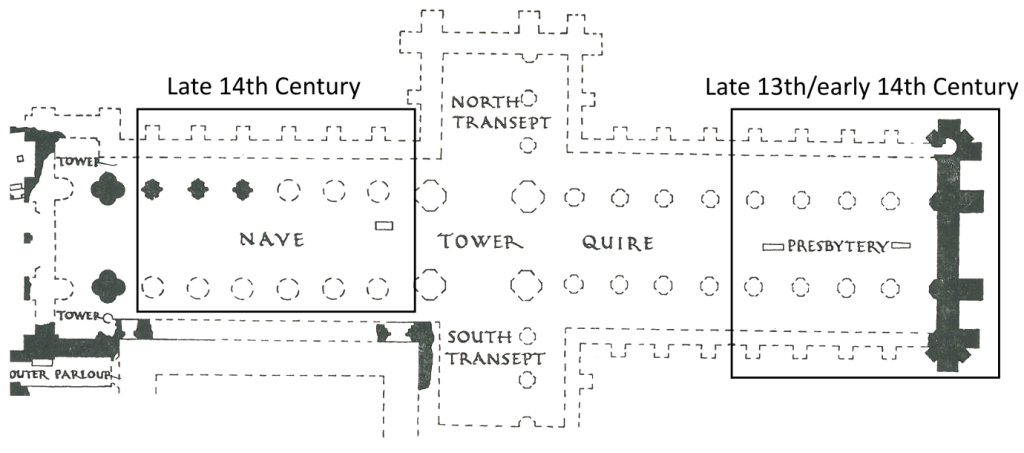

Although the Church which caught fire was finished around 1250, the east end had been extended by about the year 1300 and the west range which is visible today was newly built by 1302. It is therefore very likely that at the time of the fire in 1289 the Church was undergoing, or just about to undergo, significant building works. In addition, in the year 1295, Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale, died in Scotland and was buried in the Priory church, almost certainly with some pomp and ceremony.

Most of the outside of the church seemed to survive the fire, the magnificent West end, with the huge rose window, appears to have been unscathed but most of the interior of the nave was rebuilt, although only after the east end of the church, which, as already noted, dates from around 1300. The north wall of the nave was rebuilt on the 12th century foundations and the nave piers were built in the late 14th century. The north aisle vault may have been among the last to be completed.

Plan © English Heritiage

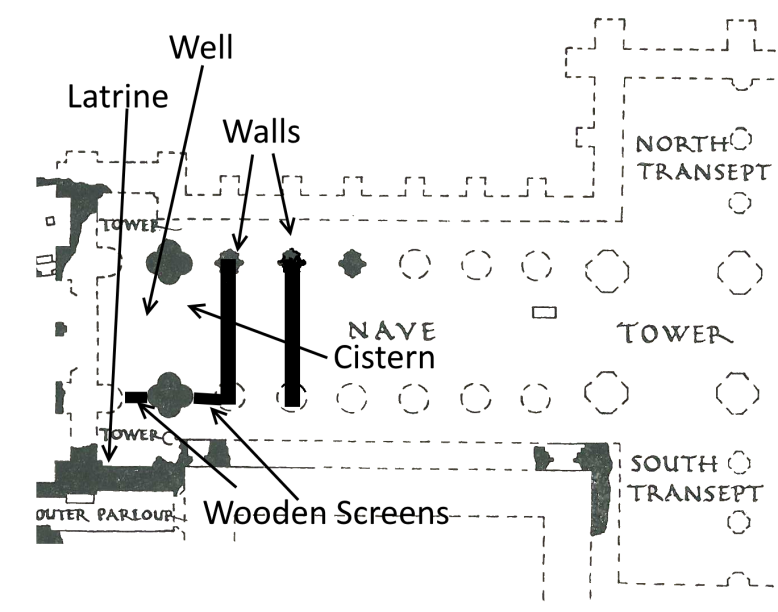

The rebuilding work began by demolishing the third pair of piers from the west and replacing them with a substantial, though temporary, wall the full height of the nave. This was done to allow worship to continue in the eastern part of the church. There were no equivalent walls between the nave and the north and south aisles which may have had wooden screens or possibly the south aisle was left open as a passage to the west range via the western processional doorway.

This was followed shortly afterwards by a second wall slightly further to the west. Again, the wall covered the nave but not the aisles, which in this case were screened with wood, but by this time a workspace was being created. A latrine was installed in the southwest tower, and a 5m deep well dug through the nave floor which fed a nearby cistern from which there were two pipes, one going out into the cloister via the processional door and the other heading west toward the west door. As there wasn’t much of a drop between the cistern and the pipes the water supply would have been fairly feeble, but probably enough to allow cement and plaster to be mixed for example. The expense and effort that went into this work suggests that it was expected that repairs would take some time and that there had been a serious interruption to the Priory water supply, which probably came from a large cistern in the centre of the cloisters. The temporary water supply appears to have gone out of use before the building work was completed, presumably once the nave was re-connected to the Priory supply.

Plan © English Heritiage

It appears that the rebuilding caused financial problems for the Priory. In 1290 the canons petitioned the king for a licence to have the income from three more churches, although they don’t seem to have been allowed this, and in 1302 indulgences were granted to anyone who visited the chapel of St Hilda, which was beside the “new hall” of the Prior’s Lodging. Special indulgences were also given to those who contributed to the rebuilding of the church.

In addition the defeat of Edward II at Bannockburn in 1314 (ironically by Robert the Bruce, a descendent of the founder) resulted in the Scots overrunning the north of England. Not only did the Priory lose the income from most of the northern estates but canons from the priories at Jedburgh, Hexham and Brinkburn were all re-located to Gisborough.

By 1328 the situation was so bad that the Priory was unable to pay the tithe (one tenth of the income) due to the Northern Convocation of Augustinian Canons (effectively the governing body) and at the same time the Priory found itself having to sell corrodies which guaranteed lay people housing and food for life.

Consequently the rebuilding appears to have progressed slowly – in 1334 Archbishop Melton of York allowed collections for the continuing repair of the church and in 1381 William, Lord Latimer, left money in his will to complete the north aisle vault along with 500 marks for a belfry. The original belfry had been in the north west tower, the interior of which appears to have been destroyed in the blaze, and which was replaced by a new belfry.

The Black Death, which occurred in 1349 and again in 1361, will only have added to the problems. Whilst the exact effect on Guisborough is not known, the outbreak is thought to have killed anywhere between 30% and 50% of the population of the country as a whole.

Conclusion

Although Walter of Hemingbrough states that the church was destroyed completely it appears that most of the earlier church, including the west end, was re-usable. Currently the effect of the fire on the rest of the priory complex is not known, and it is possible that the re-construction of the whole site, including the east end and also the cloister, which began in the very late 1200s, was planned before the fire. However, so far as the nave is concerned, a picture begins to emerge of a church whose roof was seriously damaged but whose walls survived relatively intact, apart from the north aisle. There was falling masonry; fire damage on the floor of the nave, possibly caused by burning roof timbers; bells were destroyed and at least some of the piers in the nave supporting the roof may have been seriously damaged. It is quite possible that, once the fire had been extinguished, Gisborough Priory was at least as badly damaged as the south transept of York Minster following the fire in 1984, although restoration took a lot longer as it is clear that this was a long and expensive business at a time when the Priory’s finances were at possibly their weakest.

Bibliography

Coppack, G., Gisborough Priory, English Heritage, 1993

Gilyard-Beer, R., Gisborough Priory, Cleveland, Department of the Environment: Ancient Monuments & Historic Buidings (Reprinted 1974)

Harrison, B. J. D & Dixon, G (eds) Guisborough before 1900, Guisborough 1981

Heslop, D. H., Excavations within the Church at the Augustinian Priory of Gisborough, Cleveland 1985-6, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, 67, 1995

Ord, J. W., The History and Antiquities of Cleveland, London, Edinburgh & Stokesley 1846

Pevsner, N. The Buildings of England Yorkshire: The North Riding, Penguin 1966

St John’s College website (http://www.joh.cam.ac.uk/biblia-gisburne) accessed Feb 2016