Although it was dissolved in 1540 several books are known to exist which were once owned by Gisborough Priory. Most are service books and liturgical calendars and in various libraries and collections around the country. However, the Gyesburn Bible stands out as being a richly decorated hand written copy of the Vulgate bible given to the Priory in 1333. The flyleaf contains an inscription, partly erased, in a large hand which reads “Liber sancte marie de Gyseburn” a book of St Mary’s of Gyseburn. Guisborough was known as Gyseburn in the medieval period and the Priory was dedicated to St Mary.

St John’s College, Cambridge have owned the bible since 1635. Before then Thomas Wriothesley, 4th Earl of Southampton, owned it. He acquired it as part of the William Crawshaw Library[1].

A Latin inscription at the foot of f.1 records how the Priory came to have the bible. “Clausa testamenti Magri Roberti de Pykering quondam Decani Ecclesie beati Petri Ebor. qui legauit hunc librum prioratui de gyseburn Et obiit die Jouis ultimo die mensis Decembr. a. d. millesimo cccmo xxxiido. Item do lego Prioratui de Gyseburn. Bibliam meam meliorem pro eo quod libri monasterii fuerunt combusti in combustione Ecclesie suel ita quod faciunt anniuersarium meum singulis annis inperpetuum in Conuentu.”[2]

This can be translated as “A clause of the will of Master Robert de Pykering late Dean of the Church of Saint Peter, York, who bequeathed this book to the Priory of Gisburn and died on Thursday the last day of December in the year of our Lord 1332. Item I give and bequeath to the Priory of Gisburn my better Bible because the monastery’s books were burnt in a fire at your Church on condition that they keep my anniversary each year for ever in the Convent.”

In 1289 Gisborough Priory suffered a serious fire in which many books were lost along with vestments and statues and the Priory church was badly damaged[3]. It took almost 100 years before the damage was repaired and several appeals were made for people to give money to the Priory, but the bible was also amongst the many books which would have been given to restore the lost library. The donor, Robert of Pickering, was a prominent medieval clergyman and Dean of York from 1312 to his death in 1332 and his brother, William, had been Dean before him[4]. The prime motivation in the 1300s for giving to the church was for the benefit of one’s soul, but in this case there was a family connection as well. It was common for those entering the clergy to adopt their birth place as their surname, and Robert of Pickering’s family name was de Brus, so he was a direct descendent of the founder of the Priory[5]. He probably knew Gisborough Priory well as his father, Adam, was known to a former Prior of Gisborough, Ralph de Irton, when he was Bishop of Carlisle and it is possible that Robert attended school at the Priory[6].

By permission of the Master and Fellows of St John’s College, Cambridge

Robert describes the manuscript, which was copied on vellum, as his best bible and certainly the quality of the workmanship is high. It is 13th to 14th century in date[2], so he may well have had it from new, but there is no indication as to where it was copied. The Canons at Gisborough would have been copied many manuscripts and bibles such as this, and whilst it is tempting to think that it was made there, because of the family connection, there is no evidence for this.

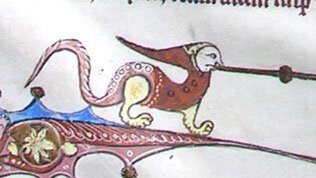

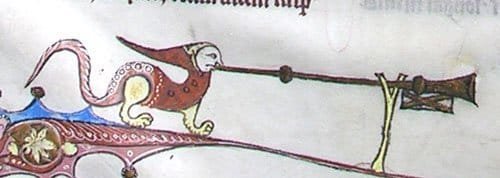

The decoration of the Gyesburn Bible is quite striking, each book has a large illuminated initial letter and many of the chapters also have an illuminated letter, often in red with green detail or blue with red details. There is also a collection of fantastical creatures (known as grotesques) which appear in the borders and the whole bible is of high quality. There are copious marginal notes, mostly readings to assist the scholar, which appear to be in the same hand as the original scribe[2].

The bible appears to have remained with the Priory until the dissolution in 1540. Another name to appear in the manuscript is that of Christopher Malton[2] and a Christopher Malton, priest, appears in a list of the former Canons as receiving a pension of £5 6s 8d[7]. It seems a reasonable assumption that it was this Christopher Malton who took the bible with him in 1540. By 1552 he was said to be “dwelling in Lyllye in Hartforthshire”[8] and appears in a list of former Canons who were complaining that their pension was in arrears by as much as eighteen months.

The Gyesburn Bible was also known to have been in the possession of a Mr Fawcitt of York as a cryptic note reveals:”Christofer Lyndley of Laughton Preacher borrowed this bible ye xxth of december 1594 of mr ffawcit of yorke for one hole yeare and gave him for it in Pawnt one Angel in gold to be restored to hym agayne when the buke is required after the twelvemonnthe”[2]. An Edward Fawcett was a Notary Public and Protector of the Consistory Court of York in 1576 but we know nothing more of Christofer Lyndley nor which of the many Laughtons is referred to. The inscription was later crossed out, but whether this was because the bible was returned or a later owner felt it was no longer applicable is not known. In 1594 an Angel was valued at ten shillings.

By 1613, and only 73 years after Gisborough Priory had been suppressed, the Gyesburn Bible was in the collection of William Crashaw. William had acquired a vast collection of early books and manuscripts, largely while he was serving as preacher to the Inner and Middle Temples in London. He had even had to extend the official lodgings to accommodate the collection. However, his style was controversial and in 1615 he was forced to move away from London, eventually dying of the plague in Burton Agnes, Yorkshire. He sold his entire collection to the Earl of Southampton, Henry Wriothesley, who arranged for it to be transferred to St John’s College Cambridge, which both he and William Crashaw had attended. This was carried out once the college had built what is now known as the Old Library, completed in 1626, to accommodate the collection. The Gyseburn bible has remained at St John’s College ever since[1].

The Gyesburn Bible was catalogued for St John’s in the early 1900s by the eminent medieval scholar M R James, who is probably best known for his ghost stories such as “Oh Whistle and I’ll Come to You, My Lad”, “The Stalls of Barchester Cathedral”, “Lost Hearts” and “The Mezzotint” amongst many[2].

- St John’s College, University of Cambridge William Crashaw’s Library, Retrieved 13 September 2019 from https://www.joh.cam.ac.uk/index.php/library/special_collections/early_books/crashaw.htm ↑

- St John’s College, University of Cambridge Biblia (Gisburne), Retrieved 13 September 2019 from https://www.joh.cam.ac.uk/index.php/library/special_collections/manuscripts/medieval_manuscripts/medman/C_24.htm ↑

- Ord, J. W. History of Cleveland (1846) pp 194-195 ↑

- Genuki (28 May 2019) York, Deans Transcription, Retrieved 13 September 2019 from https://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/YKS/ARY/York/YorkMinsterArchbishops_3Transcription ↑

- Blakely, Ruth Margaret (2000) The Brus family in England and Scotland 1100-c.1290., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1594/ pp 211-213 ↑

- Watson, John M., Genealogical Rambling (27 June 2014), Brus of Pickering, Retrieved 13 September 2019 from https://johnmwatson.blogspot.com/2014/06/brus-of-pickering.html ↑

- Surtees Society. Guisborough Cartulary. Vol 89 pp xxxv – xxxvi ↑

- ‘Houses of Austin canons: Priory of Guisborough’, in A History of the County of York: Volume 3, ed. William Page (London, 1974), pp. 208-213. Retrieved 23 March 2018 from British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/vol3/pp208-213 ↑