From the earliest days Gisborough Priory Project has sought to restore and open to the public the historic Priory gardens. The Monk’s Walk was one of the very first targets. This article examines the history and development of this iconic garden feature.

Following the dissolution of the Priory in 1540 King Henry VIII leased the estate to Thomas Leigh. Leigh was one of the King’s Commissioners and heavily involved in the whole process of the dissolution of the monasteries. He died in 1545 and two years later Thomas Chaloner married his widow, Joan. He also took on the remaining lease and bought the estate outright in 1550.

The First Garden

For about one hundred years the Chaloner family lived at Steeple Claydon in Buckinghamshire and in London. At first, they only made occasional visits to Guisborough, but, in the 1650s, the family moved to the area. At first, they lived at Park House, to the North-East of the town. Later they moved into the town itself and built a new mansion (the “Old Hall”) on Bow Street. The Chaloners also landscaped the Priory ruins creating the formal gardens seen in the print by Knyff of about 1709.

1720s to 1820

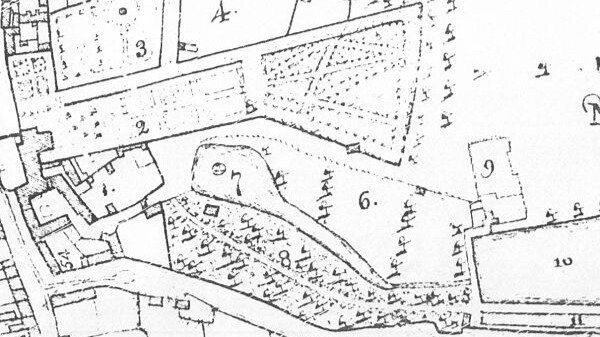

Inevitably, gardens change very quickly with fashion. The map of 1773 shows that the family had made major changes to the layout of the formal garden. This now covered a much bigger area; the most impressive new feature being the Monk’s Walk. This is the diamond shaped series of paths crossed by shorter paths on the right-hand side (the East) of the map.

Walks of this type were very popular in the early 18th century. Many authors published books giving advice on their planting and maintenance in this period.

At the same time, the terrace leading from the Old Hall to the gardens became longer. In 1773 it stretched beyond both the Priory ruins and the later wall which is the current end point.

The Monk’s Walk – Design and Construction

The Monk’s Walk required a considerable amount of levelling as the gardens slope a surprisingly long way from north to south. The 18th century gardeners had a lot of work to do to build up a level site. Archaeologists found 0.7 metres of garden soil beneath the southern apex of the Walk. This garden soil was on top of a thick layer of earlier soil with no sign of the natural ground level. There was no sign of a retaining wall to stop the soil from slipping down the slope.

The design carefully places the walk between the newly extended terrace to the north, a natural scarp to the west and the garden perimeter to the east. This allowed an exact alignment, creating good views of the Priory East End in one direction and the Old Hall in the other. The Old Hall no longer exists but the views of the Priory have been opened up once again.

At first the Monk’s Walk was an open pathway, possibly grass. However, from a very early stage the paths had a covering of pink shale, probably from the Chaloner’s jet mines at Belmont. The double avenue of lime trees came later, but the earliest trees may date from the 1720s and would have been 5 – 10 years old when planted. At first the trees were pollarded (kept to a low height) to reduce their height and to maintain good views. This practise seemed to stop in the mid-18th century when it went out of fashion. It was, however, a deliberate policy from the start not to plant trees close to the apexes of the walks to allow the best views.

1820s – A lean time for the Monk’s Walk

There is evidence of some later patching to the pink shale with yellow sandstone, and there is also evidence that the Chaloners planted new trees in the mid-19th century. These are the trees which are straight as they have not been pollarded, unlike the older, forked trees.

In the 1820s the Chaloner family suffered some rather unfortunate changes in circumstance. The Old Hall, built too close to a spring, became uninhabitable due to damp. As a result, the family had to sell the house for the materials and move to Long Hull, a little further from the town. This subsequently became the current Gisborough Hall. Shortly afterwards Robert Chaloner I went bankrupt when a York bank, in which he was a principal, failed. This resulted in the family leaving Guisborough and living in Ireland for a while. Robert was eventually able to pay off his debts and returned to England, but he never came back to Guisborough.

1850 -1930

His son, Robert II, however, did return to Guisborough. He also benefited from the coming of the railway and the discovery of iron ore on the estate. The plan of 1854 shows that Robert II made significant changes to the garden and the Monk’s Walk had lost the paths crossing the centre. It was at around this time that the planting of the replacement trees occurred. It might also have been at this time that topsoil replaced the pink shale. The topsoil remains to this day.

Once Long Hull became established as the main home the gardens around the Monk’s Walk changed in nature. Greenhouses and hot houses placed around the walls grew tomatoes and other tender plants. Despite this the Walk remained an important part of the gardens.

Just before the First World War a Mr Clarkson leased the gardens. As a tenant, not an employee, he had to make a living from the gardens as well as looking after them. In 1932 the Chaloner family placed the Priory church and cloister into the care of the Ministry of Works. Part of the gardens became a market garden and another area developed into small business units. In 1960 the Parish Church built a hall on Bow Street, on land which had been part of the gardens.

Gisborough Priory Project – The Monk’s Walk Reborn

In 2007 Gisborough Priory Project signed a lease with the landowner and were able to begin work on the Gardens.

One of the main aims was to rediscover the historic gardens around the Monk’s Walk and to open them up to the public. However, this needed a lot of background work to support it. The group arranged for reports on the archaeology, the state of the trees and from a landscape historian amongst others. This essential work helped Gisborough Priory Project to understand what was involved and where to begin.

In the first two years volunteers, with the help of the community payback unit of the Probation Service, put in over 7000 hours clearing the site.

The photographs show the amount of work undertaken to achieve this task. The thousands of snowdrops which appear every spring in and around the Walk are very popular; there is often a special opening for visitors. The many benches which the Priory Project has installed, with fine views of the grounds, are also popular.

There is now a small memorial in the centre of the Monk’s Walk, consisting of some architectural fragments and covering the burial place of the cremated remains of the bodies found in the aisles of the Priory Church during a major excavation in 1985-6. A local Catholic priest conducted the ceremony.